Biography

Giambattista Pergolesi, " whose life burned and was consumed in a flash" was an Italian composer, whose early death cut short a brilliant talent. Sometimes regarded as the father of comic opera, his works are notable for their sharp rhythms, their delightful melodies and their witty and characterful vocal writing. He was a composer of considerable importance in the development of Italian comic opera in the early 18th century, making a singular contribution during a remarkably brief career.

Pergolesi's father Draghi, and mother came from the Italian town of Pergola. After moving to Jesi, near Ancona, they took on the descriptive name of Pergolesi. Their only son Giovanni Battista was born in Jesi on January 4th, 1710.

Giovanni studied music in Jesi, taking violin lessons from Francesco Mondini, and showing a remarkable natural aptitude. When he was sixteen he was invited to study at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesu Cristo (Conservatory of the Poor Men of Jesus Christ) in Naples. Here Pergolesi, that all in Conservatory called "Jesi," studied music, composition and song for five years. His fees were paid by a local Jesi aristocrat who had taken an interest in the young man.Pergolesi's technical prowess on the violin and his ability to improvise his own florid passages was noted by his teachers at the Conservatorio.

In 1727, after Giovanni had been at the conservatory for about a year, the family suffered a serious blow when is mother died and her dowry went missing. His father suffered a loss of income, and the small family entered a very difficult period.

During this time Pergolesi began composing. Many of the chamber music and concerti for violins which have never been assigned definite dates and were mostly published posthumously were probably written at this time.The first work to attract attention was his sacred drama, La Conservatione di San Guglieme d'Aquitania (1731), given its first performance by his fellow students at a Naples monastery.

Also performed at this time was Pergolesi's humorous little intermezzo, Il Maestro di Musica, which was a considerable success and brought him attention of three men who became his patrons: the Prince of Stigliano (the Viceroy of Naples' equerry), the Prince of Avellino, and the Duke Maddaloni. In 1732, he became maestro di cappella to the Prince of Stigliano.

With these powerful supporters, Pergolesi was invited to repeat his theatrical success at the Naples Court. He composed the opera La Sallustia (libretto after Apostolo Zeno’s Alessandro Severo), and a new comic intermezzo, Nerino e Nibbia. These were first performed in Naples in January 1732. The opera pleased but the intermezzo failed, and the music has since been lost.

The following year was not a very good one for Pergolesi. His father died and his opera Ricimero and its intermezzo Il Geloso Schernito suffered a dismal reception. Deciding to try his hand as something other than theater, Pergolesi switched to instrumental music, composing more than 30 sonatas for violin and bass for the Prince of Stigliano. Twenty four of these were printed in London long after the composer's death. He also wrote some sacred music at his time, including a Mass to commemorate the legacy of the earthquake which had devastated Naples in the spring of 1731; it won high praise at the time but has since been lost.

Attempting to get back into the theater, Pergolesi wrote a deliberately Neapolitan flavored work Lo Frate 'Nnamorato, (libretto by G.Federico). It was first performed on September 27, 1732 and was received with great enthusiasm by the public.

A year later the opera seria, Il Prigionier Superbo appeared (August 28, 1733), accompanied by its comic intermezzo La Serva Padrona. The serious opera met with some success, but La Serva Padrona was to become the most famous of all intermezzi. It became detached from its original position in support of the serious work, and went on to win international fame, particularly in Paris. In 1752, a production of La Serva Padrona provoked a pamphlet war between the partisans of French and Italian opera (the "Guerre des Bouffons" or "War of the Bouffons") and led to the founding of French opera comique. To this day La Serva Padrona has enjoyed an audience of its own.

These two years of success were culminated with Pergolesi's entering the service of Marzio IV Carafa, Duke of Maddaloni in 1734. Giovanni traveled to Rome with his new master in 1734 where he enjoyed the privilege of having his Mass in F performed. Unfortunately, his success was short lived. Returning to Naples by mid-summer, he met with another opera seria failure when Adriano in Siria (libretto by Pietro Metastasio) was premiered on October 25, 1734, although the intermezzo La Contadina Astuta (libretto by T.Mariani) fared reasonably well.

His next production in Rome was disastrous.L’Olimpiade (libretto by Metastasio)

premiered on January 8, 1735, and so displeased the crowd that an orange was lobbed at Pergolesi's head. He responded by placing his next production, an opera buffa entitled Il Flaminio (libretto by Federico), in Naples. This spirited and airy three act comedy met with success and is still occasionally revived. It was, however, to be his final opera.

By now Pergolesi was aware of something seriously wrong with his health, and his remaining time was spent attempting to put his affairs in order.Years of fast and reckless living had weakened his resistance to infection, and he was now in the grip of consumption. The Duke of Maddalon allowed him to become a house guest of the monks of the brotherhood of San Luigi di Palazzo at their Franciscan monastery in Pozzuoli in the early months of 1736. Pergolesi left Naples having instructed his aunt to take possession of any property he left behind; he clearly did not expected to return to Naples. He died in Pozzuoli on March 16th, 1736 at the age of 26.

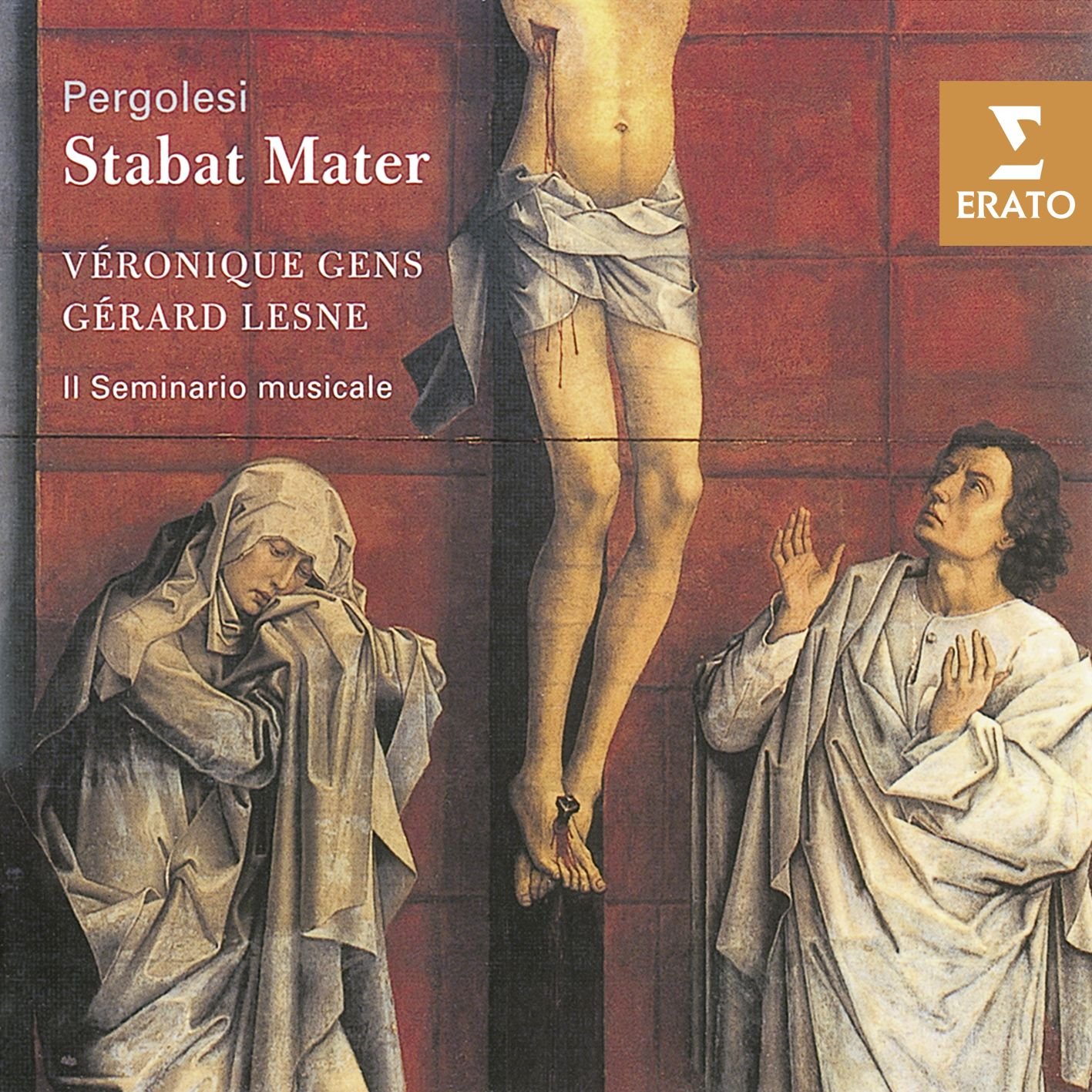

After Pergolesi's death, his setting of Stabat Mater, a Latin poem attributed to Jacopone da Todi, was quickly recognized as something out of the ordinary and achieved an international reputation.Legend has it that it was written at Pozzuoli in 1736, for the monks of the brotherhood of San Luigi di Palazzo, during Pergolesi's final months of retirement in anticipation of his death. However, it is probable that this story stemmed from a misinterpretation of an inscription on the autograph score, now residing in the library of the Abbey of Montecassino. An examination of the manuscript shows that the Stabat Mater was written over a period of time, possibly beginning as far back as 1729, and was composed in separate spurts of creativity separated by long periods.

Many arrangements were made of it, J.S.Bach transforming it into his motet Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden.It has attracted its critics as well as its passionate admirers, and shows the operatic background of the man who composed it, but as one of its later re-arrangers, John Adam Hiller, commented: "The man who could remain cold and unmoved when hearing it does not deserve to be called a human being".

La Serva Padrona in Paris precipitated the "Guerre de Bouffons", the name given to one of the most remarkable episodes in operatic history, when all of Paris was divided from 1752 to 1754 between the supporters of traditional French serious opera as exemplified by Lully and Rameau, and those of the new Italian opera buffa as exemplified by Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona. The traditionalists included Louis XV, Madame de Pompadour, the court and the aristocracy; on the other hand, the queen and the intellectuals (particularly Diderot, Rousseau and d’Alembert) supported the Italians for having breathed new life into a moribund and stiflingly conventional form. Rousseau’s contribution (in addition to composing operas in the Italian style) was his famous Lettre Sur la Musique Française of 1753.